The Impact of Mayoral Re-election on Violence and Collusion in Mexico

The Key Takeways

Being able to re-elect (or reject) an incumbent is a critical aspect of democratic accountability. Voters can hold elected officials accountable for their actions, and officials, in turn, govern better or more in line with what voters want in order to win re-election. But wanting to continue holding office can also drive officials to work with powerful groups, embezzle campaign funds, and use their official authority to keep their position. It can also incentivize armed groups, like criminal organizations, to use violence and coercion to keep key allies in power. What happens when mayors, particularly in areas where criminal organizations are powerful, gain the ability to run for re-election?

This is what happened in Mexico in 2018, where mayors in some states where permitted to run for re-election ahead of mayors in other states. The same year, Mexico experienced a record level of violence against local politicians, only to be surpassed again in 2021, with hundreds of mayoral candidates murdered, abducted, or threatened by organized crime. Criminal-electoral violence like this, as well as collusion between elected officials and criminal groups, present key challenges to democracies across Latin America. Despite this, we understand little about how political incentives shape the behavior of organized criminal groups.

In my forthcoming article at the British Journal of Political Science, titled “Defending the Status Quo? How Re-election Shapes Criminal Collusion in Mexico,” I examine how the introduction of mayoral re-election affects electoral violence and local collusion between mayors and criminal organizations in Mexico. I compare municipalities where mayors were eligible for re-election to those where they were not using a staggered difference-in-differences design. My findings suggest that in places where criminal groups already influence local politics, re-election caused increases in killings of candidates who rivaled the sitting mayor, and caused an increase in collusion following the election. This is driven by efforts of criminal groups to keep key allies in power, providing continued protection and resources from state channels. You can read the full paper and appendix here.

What was the Reform?

In 2014, Mexico implemented a reform that permitted state legislatures to allow mayors to run for immediate re-election. This change aimed to reduce corruption, improve governance, and promote local accountability, while also maintaining local party power. However, it also created an environment where some mayors—especially those in areas where armed, criminal groups are powerful—may feel pressured to make deals with criminal organizations to secure their legacies and stay in office.

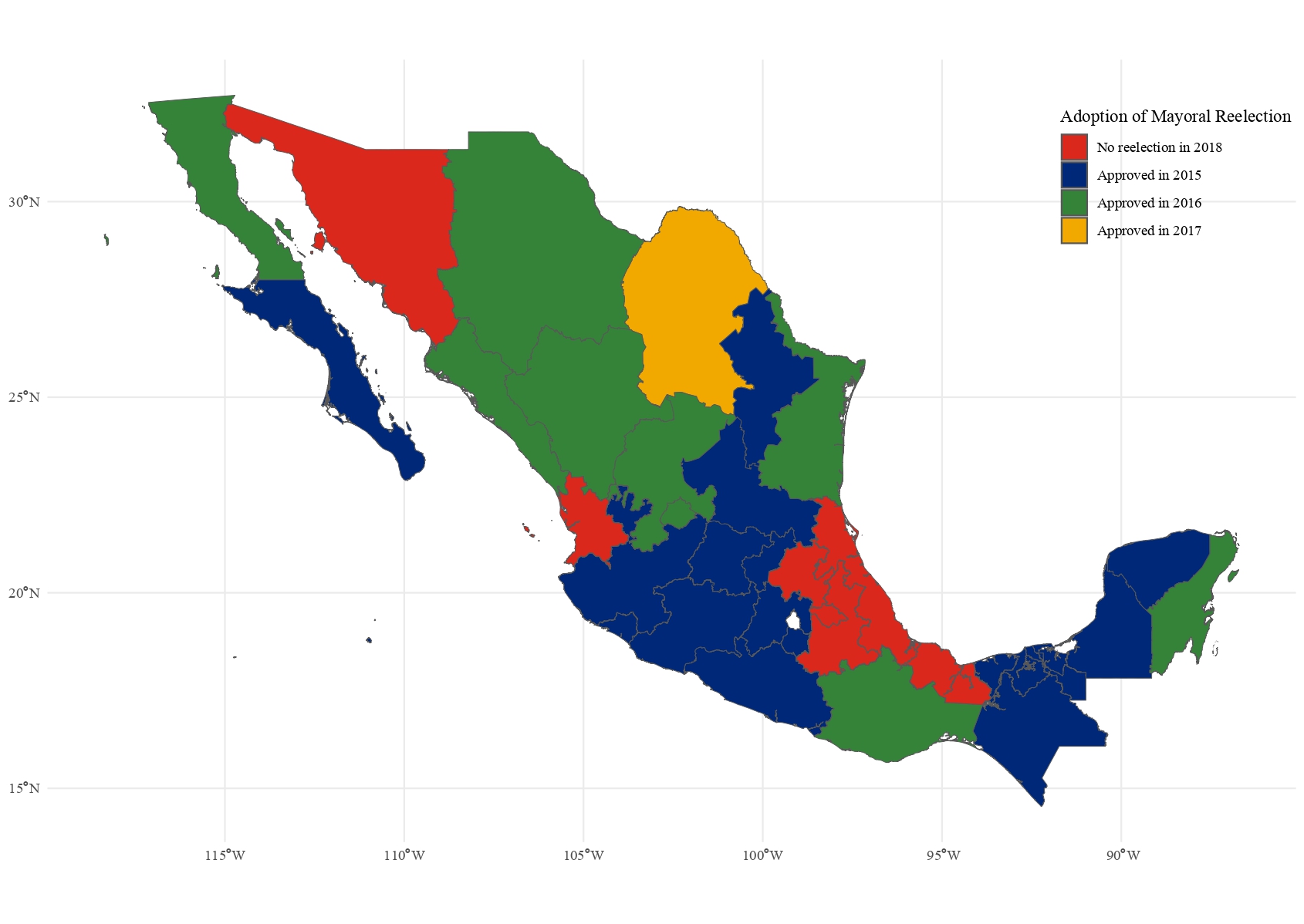

Following state legislative calendars, states began to approve mayoral re-election in 2015, 2016, and 2017, effective for the nationally coordinated elections in June of 2018. Here’s a map of these approvals:

To learn more about the reform, check out Motolinia (2025). In some states, mayors could only serve consecutively twice, while in others, they could hold office up to four terms (twelve years in total).

How did the Reform Affect Electoral Violence and Local Collusion?

I compare how the introduction of mayoral re-election changed two outcomes: first, how organized criminal groups used violence to shape electoral outcomes, and second, how mayors and criminal groups colluded following elections, using original data on violence, municipal audits, and national surveys from 2012 to 2022.

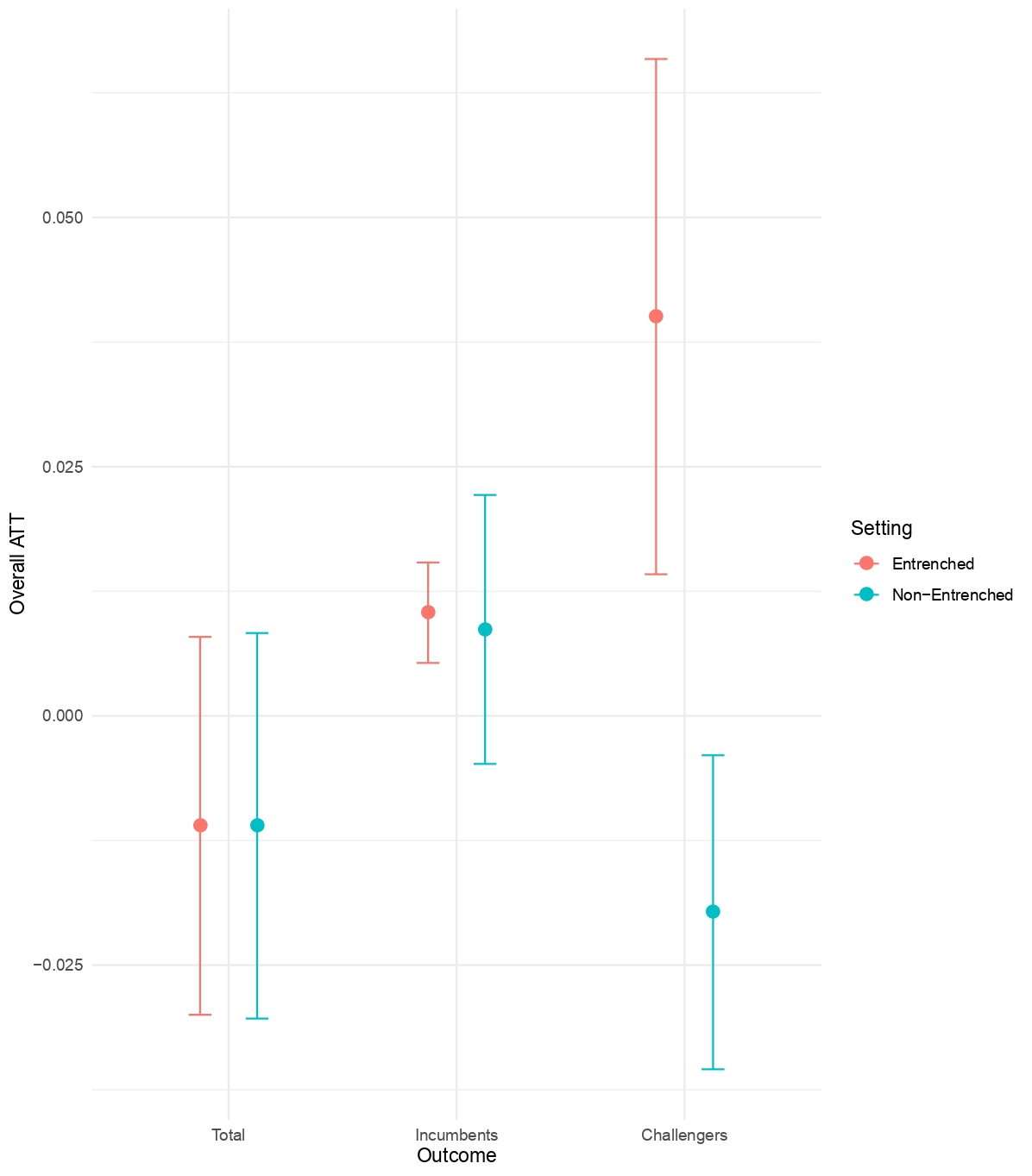

The results show that, when mayors can run for re-election in places where criminal groups are powerful and entrenched in local illicit economies, they are also significantly more likely to kill candidates that challenge the incumbent mayor. Using a conservative proxy for criminal entrenchment in local politics (presence of poppy fields), I show that organized criminal groups use electoral violence to ensure that their preferred candidate gets into and stays in office, allowing continued benefits of co-opted governance. Here’s a visualization of the effects of the reform by victim:

When mayors can run for re-election in areas where organized crime already shapes politics, these municipalities are 79% more likely to be selected for budgetary audits by La Auditorıa Superior de la Federacion (ASF), an independent auditing body that selects municipalities based on their likelihood of corruption and mis-spending. These audits also reveal an average 74.7% increase in improperly allocated municipal spending, suggestive of corrupt practices.

Localized survey evidence from Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) also shows that in these high-crime areas, mayoral re-election causes increased perceptions of police corruption, while electricity and water provision remain consistent. Further, criminal groups are more stable and cohesive in these areas, benefiting from protection and resources by local mayors.

Is Re-election Good for Democracy? How can we better protect officials, candidates, and voters?

The short answer is yes. Re-election is core function of democracy, where voters can have their voices heard and hold elected officials accountable. But the guardrails that protect these mechanisms must reflect the local challenges and dynamics that threaten these democratic pillars.

In high-crime areas, where criminal organizations co-opt and capture state actors and functions, institutional reforms like re-election can also be captured and distorted for illicit gain, thereby undermining the positive effects of democratic rule. This poses a key challenge for democracies that face problems of organized crime: state governance can become a vessel for criminal governance, where spending, police power, and state authority are directed away from helping communities and instead to growing illicit networks.

In these settings, reforms should come with guardrails that consider and account for these risks appropriately, like providing increased protection for candidates running for office and federal attention to dismantling recruitment networks, illicit profit flows, and trafficking routes that propel criminal actors. Other measures also include strengthening and coordinating oversight, transparent audits, and non-partisan investigations to prevent collusion from taking root.

More broadly, this also suggests that academics should consider criminal groups as powerful political actors, particularly in settings such as Mexico, Brazil, and Ecuador. While they may not boast clear partisan ideologies or allegiances, they fundamentally shape who gets into office and how they govern. By expanding our conceptualization of which groups are inherently political, we can better generate knowledge about their impacts on governance and better inform policy to protect human security and dignity.